“Make sure you’re home before the street lights turn on!” — any mom, circa 1975

As a child, I and my parents roamed for miles if we wanted with only our bikes or a bus pass and a few coins in our pockets. By the time my children were born, parents were getting turned in to the police for letting their kids play at a public playground unsupervised. Within a single generation, we went from free range, latch-key kids to X-box and playdates. Basketball hoops in the driveways were verboten by most HOA’s. Gaming replaced biking and yard lot baseball. Childhood obesity has soared along with depression rates and social media bullying. School traffic is a mess because no one even trusts a school bus, much less walking.

How did we get here?

Little House on the Prairie vs. America’s Most Wanted

One of the biggest differences between those in Gen X and the Millennials was our entertainment options. Growing up, Gen X and their parents were socialized by programs like the Walton’s, Little House on the Prairie, and Happy Days.

This wasn’t just what we saw on TV. These were the patterns our parents grew up with. We watched Laura Ingles and her siblings walk through fields and snow to get to their one-room schoolhouse and heard our grandparents talk about doing it themselves. The Fonz and Ritchie Cunningham ran a tamer version of West Side Story. Getting themselves a flashy ride of their own was a rite of passage—and by no means guaranteed. Even mom rarely had a car or a job—that inflection point came in 1980.

The typical 2-mile walk zone was set during the mid 60’s in Florida. By first grade, nearly all kids were assumed to be able to walk that far and back without assistance (Kindergarten wasn’t mandatory until the mid 70’s in most states). We literally had parents that would tell us to go outside and play—and then lock the door to make sure we did. As moms went to work in the 80’s, most school age kids were left at home alone after school—creating a different type of latch-key kids.

All that changed with the abduction and murder of Adam Walsh in 1981. They found his severed head within two weeks but never found his body. It took nearly 20 years to find his killer. By the mid-80’s there were hotlines for missing children. Parents began to warn their kids of “stranger danger”. The media declared that up to 50,000 children were abducted annually, failing to mention that less than 1% of them were stranger abductions—a mere 67 cases in 1984. Most of the social changes didn’t take root until John Walsh started his weekly TV program, America’s Most Wanted, in 1988.

This coincided with the advent of digital entertainment. I won an Atari when I was in high school in the mid-80’s. My parents would never have bought one. We started using Radio Shack Trash-80’s (an early PC) in middle school, but the most that was good for was scrolling your name on the screen or writing papers. Tetris was high tech. By mid 90’s, Nintendo and X-box were in high competition mode and everyone had one. It wasn’t safe to go outside but there was plenty to do inside and these digital resources became a convenient form of childcare for many.

Nowhere to go

At the same time, the built environment was changing. Although zoning was established in the 1926 Supreme Court ruling, Euclid vs. Ambler, there wasn’t much time for it to take root before the great depression and WWII. The first subdivisions built after WWII were more curvilinear still pretty well networked. The early Levittown subdivisions look like TND paradises in comparison to today’s projects.

The block lengths were getting a bit long in the tooth by the 50’s, but the connectivity was pretty good and fences were rare—lots of unregulated communal space for unstructured play.

By the 1970’s, cul-de-sacs and clusters were the predominant pattern.

Ideally, kids could play together in their own cul-de-sac if the neighbors didn’t complain, but it was a long way from there to anything interesting. My mother-in-law described being able to walk to the pool, library, theater, school, and downtown from her childhood home up on the hill in Steubenville—a rust-belt, Ohio River town. By the time I was growing up in the 70’s, it was 2/3 of a mile to the convenience market and it felt like a rite of passage to be allowed to go there on my own (at 5 years old). There was a playground across the street, but nowhere else that made sense to go to. By the time my oldest was that age, it was 2.5 miles to the closest grocery store and he would have had to cross a 4-lane highway to get there. We had a pool for our subdivision, but rarely visited it. I didn’t necessarily stop him. He had no desire to leave his video games. (I’m not sure he even does now at 23). The subdivision layout was not that different from the Curvilinear pattern used in Levittown, but the land use was so tightly zoned and retail was so large in scale that there was nowhere to go.

How do we get out of here?

A subtle shift from an unexpected direction.

Although the development community hasn’t quite figured it out yet, we’ve gotten a huge break in the last decade—and Amazon is at its core. With the advent of home delivery, big footprint retail just isn’t relevant. I have a marketplace that spans the world at my fingertips. Why would I need a mall or a superstore locally? On the otehr hand, local retail is more relevant than ever.

What consumers need locally are the things that Amazon can’t provide. That comes in three varieties: urgency, uniqueness, and community.

Urgency: Sometimes you need something right away—a cup of sugar for a recipe or a bag of ice for a party. Amazon is fast and getting faster, but not “run to the corner store” fast.

Uniqueness: Some goods are mildly exotic or need to be picked out by hand, like getting the right shade of bananas or a comfortable shoe. The grocery stores and hardware stores have caught on and are rapidly downscaling and distributing throughout the landscape (shoe stores are still clueless). Dollar General’s are popping up at the edges of the subdivisions and though they get a hefty battle on the front end, they get heavily used once they’re in place.

Community: Some of us still like the browsing or going out to eat because it’s a social activity—a third place or a time spent with a friend. The quaint downtown areas are filling that niche.

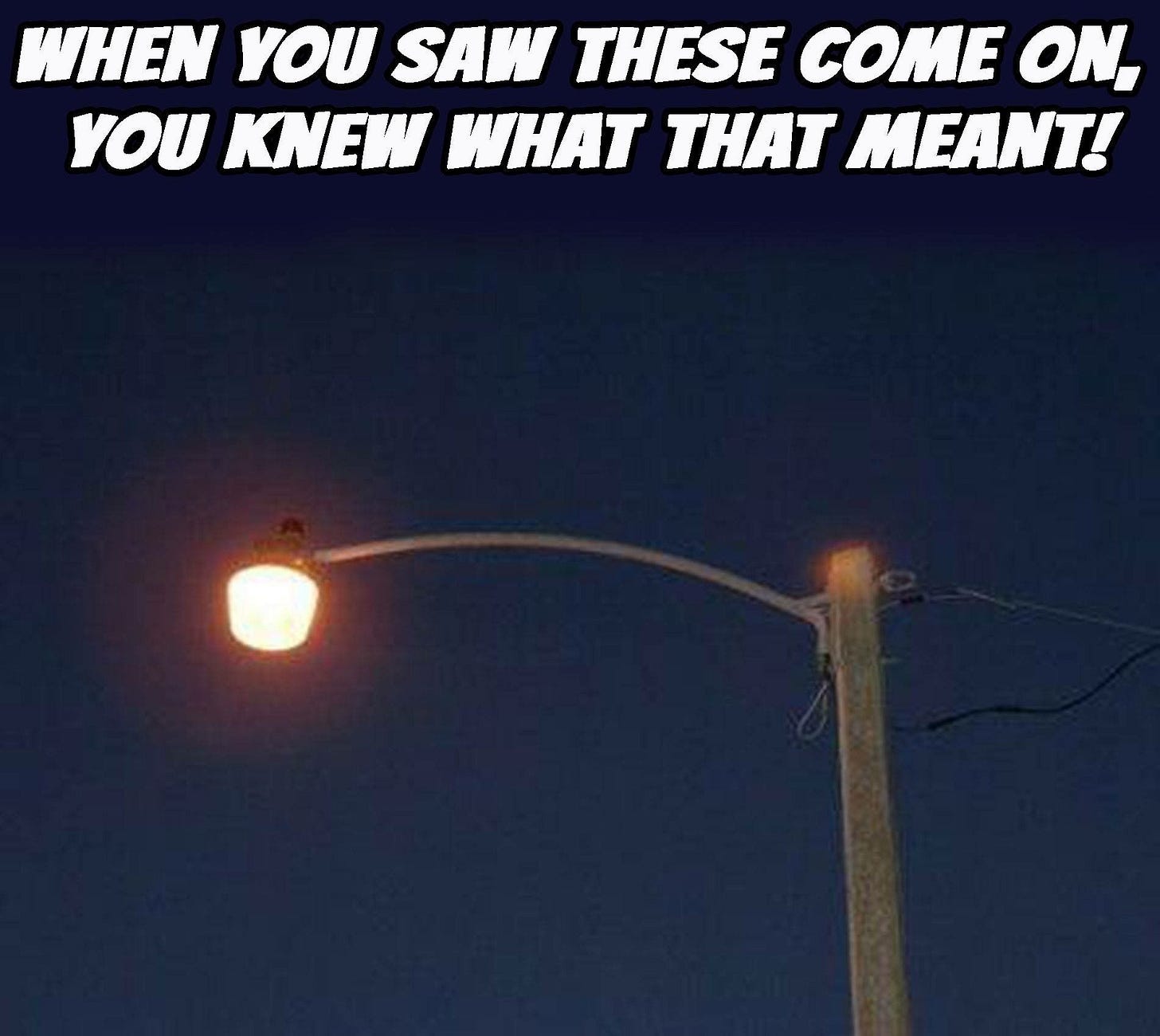

All of three of these are niches that only local scale retail can fill, but they also require that the retail form is a lot smaller and a lot closer to home. The general store model that Target, WalMart, and Meyer’s serve customer catchment areas of 6 miles in radius—less than 20% of that will be walkable unless you live it a major urban center and have premium transit access. Once you get onsite, you’re still limited to a downtown retail scale, which is generally 1/8th mile in radius, but the parking lot chews up a huge amount of that space. If you have to get it all done within 600 feet from the back of the store, the parking lot is going to rapidly become an annoyance. Joel Garreau found that dimension was the limit for how far apart you can place anchor stores in a mall and it still pops up in big box retail centers. When you have to regularly fight for a space in that radius, people just quit doing it—your employees can be required to park outside it, but your customers won’t. It’s uncanny how closely real life holds to these dimensions.

Local Retail is Kid Friendly

Once you get retail down to local scale and dispersed with centers every mile or two apart, you’re back in range for kids to access it independently. Adding sidewalks or bike paths in an area with robust local retail is no longer a waste of money because they’ll get used—most of all by kids. In those types of areas, we can’t just slap a bike lane on a 6-lane highway. Complete streets take skill to design or they’ll kill people. We need walking and biking networks that keep those walk distances down to a reasonable scale.

Kids are being told how important it is to save the environment. There is nothing more idealistic or evangelistic than a 3rd grader studying their ecological footprint. Parents are fighting the digital impact on their kids and sending them back out to play—with them at first, but soon enough by themselves.

Katie now walks downtown independently twice a week or more. She may never drive, but she may never need to. If it works for kids, it will work for her and for me when my body no longer wants to cooperate with me or I can no longer drive.

I see the light at the end of the tunnel here. Our kids will get their freedom back.

Later this week, we’re going to cover the next mental framework: the scale of human interaction. This is where it really gets good so you’re not going to want to miss it.