You can please some of the people all of the time,

you can please all of the people some of the time,

but you can't please all of the people all of the time

One of the Brick City Lab scenarios is a greenfield project. They get the buildings and some extra stuff and they can arrange it any way they want. I had just told them how important it was to keep things within 60 feet, so their natural response was to space the buildings that far apart. So far so good.

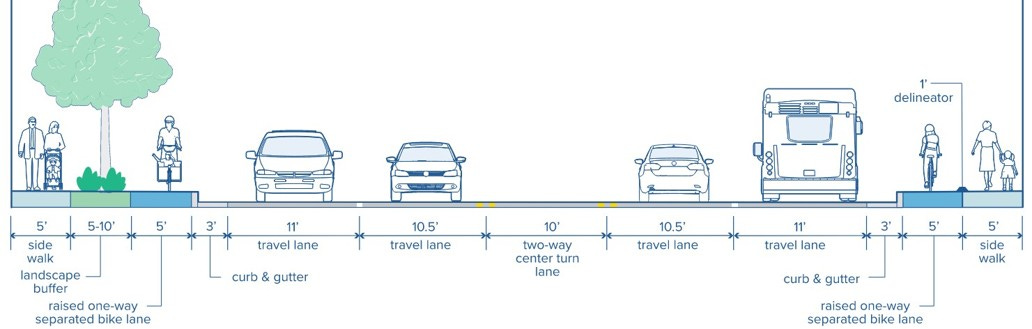

Then they proceeded to put in two travel lanes, a dedicated trolley lane and bike lanes on both sides. By the time they were done, there was only 2 feet left for sidewalks—and they really didn’t notice until we were going over the final design.

It’s easy to laugh at that now, but it’s far too easy a mistake to make, and fundamentally, that was the problem with the entire complete streets movement: The ideal robs you of the possible.

When everyone gets a seat at the table to ask for whatever they want and you only have a single right of way to keep them all happy, things are not going to end well. (That’s why I keep saying “complete streets are plural”). The intentions were good. Reality is a female dog in heat.

Here’s the problem:

When we looked at our data sample from the Naturalistic Driving Study—an experiment where cars were instrumented to the teeth and drivers just drove them for a year—there was a huge problem with a mismatch between the likelihood that a driver would see a pedestrian and the speeds that pedestrians expect to be seen. Above about 23 mph, the odds that the driver saw the pedestrians that were actually there was about 50/50. In essence, drivers had to expect to see pedestrians at least 1 out of every 4 trips through to choose those low speeds. Expectations drive everything in our brains. We will govern ourselves based on what we expect, not what we actually see or get.

Unfortunately, both designers and pedestrians expect to be seen all the way up to 40 mph or more. By the time you get to 32 mph, it’s 50/50 odds of having blood on the windshield if you get hit. We’ve talked about why drivers are ill equipped to see pedestrians at those mid-range speeds, but they believe that drivers can. For that matter, our design standards assume that as long as it’s possible to see them, drivers will actually see them—the only thing the standards worry about is line of sight.

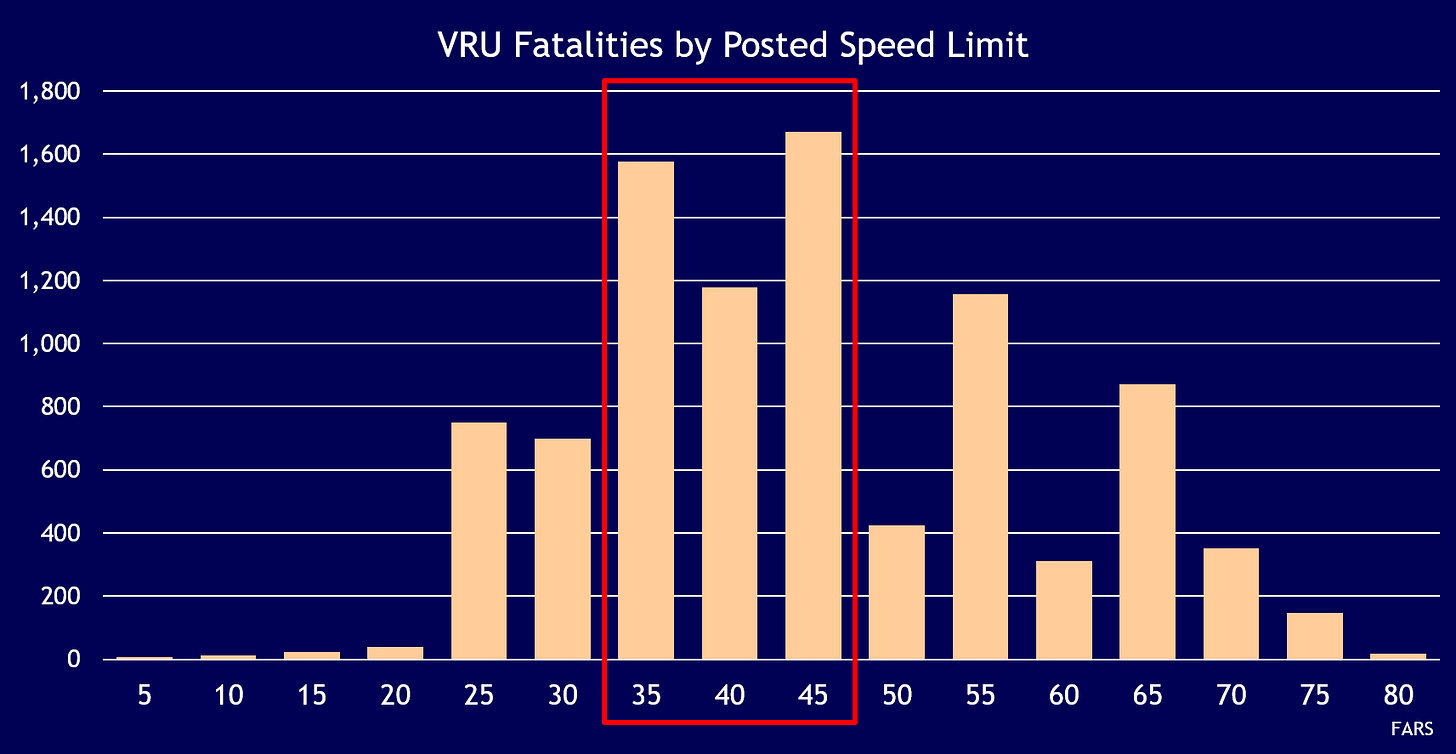

Below around 23 mph operational speed, the fatality numbers are low. Above 45 or so, the crash rates start to go back down again—because everyone knows the risks that are involved, and people are usually pretty good about avoiding those places. This graph is based on the posted speed limit, but you get the idea:

(Why anyone is walking anywhere near a road that is posted at 65 is a whole different set of questions—that’s usually a problem with vehicle break-downs—be careful out there folks).

The road to Hell is paved with…

I’m not faulting the idea of complete streets. Design for all users is a laudable goal. You just can’t do it all in one right of way. Mobility and access are at cross purposes. Our failing was to think that we could do otherwise.

So what do we do now?

We can have our cake and eat it too, but only if we think in terms of systems and network. Complete the networks, not the streets.

It destroys our credibility and erodes political will to try to put bike lanes and transit stops on arterials. I recognize the difficulties of putting them anywhere else. Again, network makes this easy and every other option makes it infinitely hard—so make yourself the network you need.

It annoys our drivers and doesn’t make a difference have collectors flanked by subdivision walls posted at low speeds. Should we all slow down? Probably. Have you given them a good reason to? No. There is an inevitable push-back that will cost us years and lives. Try getting FDOT to approve a road diet right now. It won’t matter that road diets make people money and eliminate some pretty nasty rear end crash types. We’ve burned those relationships and I don’t know how long it will take to get them back.

We have to start with “You are right, and we can do better.” Yes-and is the only way forward.

I am faulting the idea of *complete streets*. It's a pretty good, but not a great concept from an urbanist's perspective. The strength is resonance. *Complete* is a positive concept, and critiquing streets for being less than complete sounds less grumpy than the alternatives. In addition, the idea that we add something to what is already there makes street configuration appear to be non-zero-sum problems from a modal perspective. The appeal is obvious and it was a great framing for unifying activists, and it's easy to articulate.

However, the shortcoming of complete streets as a concept is that wide streets are problematic from a comfort perspective and a safety perspective. When we keep adding functions to streets, we either lose space for other functions or it leads us to making streets wider, and when the existing ROW accommodates every function, that should tell us it's too wide. We need narrow streets.