I absolutely love fireworks. It was years before we could take Katie—she needed headphones from the time she was tiny. She’s still not thrilled. I can cut her some slack on that. We get to see a lot of fireworks. The main road in our town lines is due north of the Magic Kingdom, which means we can see a fireworks show around 8:30 or 9 every night of the year.

Every year, our town has its own show, like nearly every other town in the US. Everyone gathers around the lake and hangs out for hours listening to (live?) music, hanging out, eating burgers, and just generally having a good time with our neighbors.

We live not far from the lake. We could walk there, but most folks will probably take a golf cart. The street grid around the old downtown is easy to navigate and has plenty of sidewalks. If you wanted to send your kids down to the fireworks on their own, you easily could, probably from about 3rd grade on. I suspect less than one in 10 US kids would be able to do that today. Maybe there’s more than I think. In the Orlando estimate it’s probably 1 in 50, but I suppose in the small towns and big cities, that number could be higher. I doubt it.

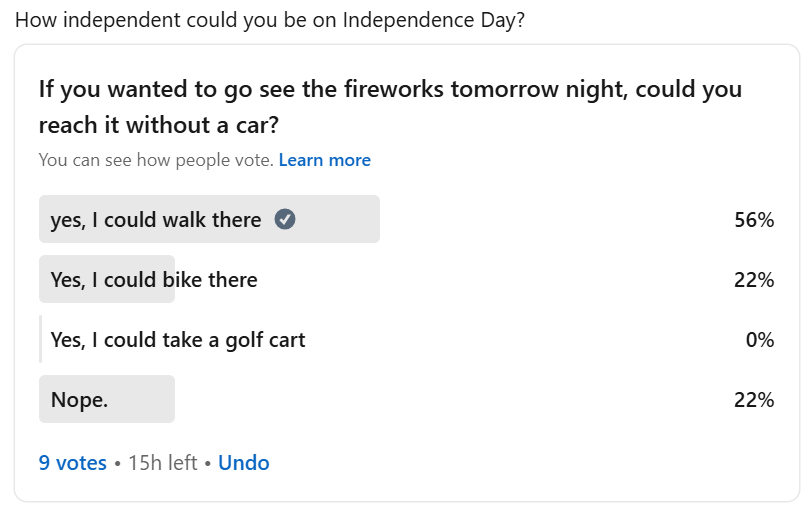

I held an informal poll on it earlier today. Now, I have a lot of urban designers and planner geeks in my connections, so it’s not exactly fair, but the results of my unscientific poll were a bit better than I expected.

How independent can you be, if there’s nowhere to go?

We often complain that kids spend too much time on video games or their phones. As a Gen X’er, our parents would literally tell us to go play in traffic. You’ll get thrown in jail for that kind of thing today. What are they supposed to do if we don’t give them anywhere to go?

Since I was about 10, I’ve lived in environments where walking or biking weren’t a viable mode of traffic—and it had nothing to do with the roadway designs around me. When it’s 5 miles to the closest anything, walking isn’t on the top of your list of travel options. I had a few years that were different in my 20’s: college, of course, and then the little coal town we lived in during grad school. Biking in Maine was great (I didn’t think so at the time), but as soon as we got out of school, we were in suburban environments. I suppose we lived close enough to a grocery store to walk for a few years, but we never did, and no one else did either. The neighborhood streets were fine, but the moment you left the subdivision, it was pretty hostile territory. There was a child killed not far from where I lived on her way to the local elementary school. That easily could have been Katie if we had still lived there. Biking through an intersection with double lefts on all 4 legs is not ideal for kids.

An Amazon Gift

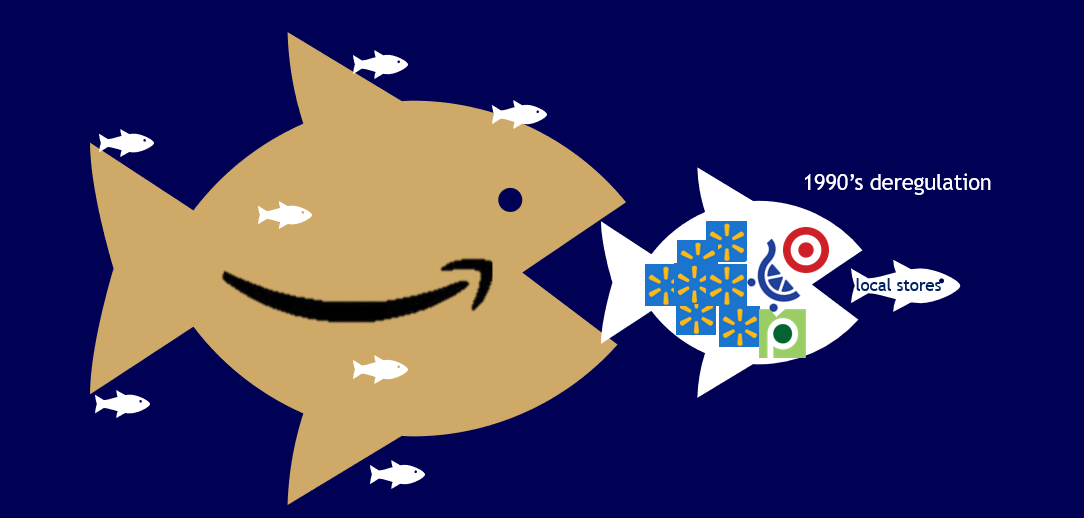

The land use is changing some, and Amazon has a lot to do with it. In the 1990’s, deregulation killed the local community grocery store. Larger chains could gobble up the little guys by cutting deals with suppliers. They could also create more sophisticated logistical supply chains, without the encumbrance of that silly anti-trust legislation. (What were we thinking?)

About 15 years ago, Amazon started chewing up all those medium sized chains. It was hailed as the death of retail. Many of the malls died, but the smaller local retailers have thrived because they can put their wares on Amazon just as easily as anyone else—like sucker fish on a shark.

The grocery chains are still working out how to adapt, so they have a new strategy. There are three things that Amazon can’t do:

They can’t get you diapers in the next 5 minutes.

They can’t pick out your tomatoes or shoes. I am returning shoes this week. I was so sure they would be fine and they absolutely aren’t.

They can’t build a relationship with you.

In response, chains like Kroger, Publix, Wegmans and the like have shrunk their footprint and distributed throughout the landscape. It used to be 5 miles or more to the closest store. Today, if you can’t get to a neighborhood grocer within a mile, you’re probably in an area that isn’t safe enough for them to keep one there—and that does still happen.

That means there are places that kids—and adults—could go within easy biking range. When things are that close together:

If you build it, they will come.

It’s gotta be safe enough for a kid, but all it takes is a handful of people who figure out that it works and a bunch of people will try it. Don’t believe me? Here’s a picture I snapped the other day on my way into my own grocery store.

Yep, that’s an e-bike. They’re cheaper than a car and will work fine for a low income family. They don’t even have decent parking for it yet. In the last few years, I’ve even seen cargo bikes showing up to church on Wednesday night with three kids in the front.

There was a time that adding a bike lane was a cause for engineers to roll their eyes and shake their heads. They’d do it because it was a federal requirement and someone would complain if they didn’t. They also knew how much those things cost. At $12 per square foot, that’s about $900k per mile for something that they weren’t even sure was safe enough to sign off on and probably wouldn’t get used.

The studies are pretty conclusive now. Separated bike lanes are so very much safer than on-road lanes, I don’t know many places I would specify otherwise if I had the choice. They feel safe enough for at least a high-schooler, and maybe even younger. If the land use were like it was 20 years ago, it still might be a waste—because there wasn’t anything close enough to get to. Today, that’s just not the case. Throw a separated bike lane up and within a few weeks, it gets regular riders. On-road lanes still don’t get used. Communities with grid street networks become a haven for riders and dog walkers. People know their neighbors again.

I don’t know if the idyllic US town was common outside of the cities. We’ve been a pretty independent lot. It takes that kind of people to settle a land this vast. When you’re giving the land out by horse race, it’s going to be a long time before density is anything but an after-thought. Having said that, there’s good reason to be hopeful.

A few weeks ago, we mourned the passing of the great illustrator and urbanist, Leon Krier. CNU posted a retrospective along with this beautiful gem:

It encapsulates the difference in structure between a walkable community and a vehicle oriented place better than I’ve ever seen.

The good news is that we can get to the first from the second. It will take a generation or more, but it can be done. It starts with a local grocery store, a commons where people want to hang out, and the walking and biking network to connect it all up. There are things that could push it along, like restricting parking or increasing density, but we can get there on our own without them.

And that day will truly be an Independence Day.