Functional Engineering

The practices of compassionate engineering

Matt Duncan looked up from his paperwork at the knock on his door. It was only 7 and the Safety Manager for Lakewood, Colorado had already been working for an hour.

“What’s up?”

“Have you made it out to see the frontage road site where that fatality was?”

Matt swore under his breath. Had it already been 4 days? He usually made it out to those sites faster than that. Things change too quickly to let it go that long. One look at his signal tech’s face showed there was another reason for concern.

“I just found out it was my sister.”

Vision zero had just gotten real.

Standard of care

As transportation engineers, we call ourselves practitioners, much like doctors or lawyers. The doctors that we idolize (and should) are the ones that don’t just manage symptoms but search out the causes of our disorders. It’s hard to get those doctors paid well enough because that process takes time and money. Most of the really good ones get (pejoratively) labeled as “alternative” or “functional” medicine practitioners which means they struggle to get listed in most insurance networks. They’re not going to do things fast and cheap, although they nearly always cost the system less time and money over the long haul.

If we’re going to make progress on Vision Zero, we need more functional engineers. It takes time, dedication, and resources, but in the long haul, our safety solutions can be a blessing in thousands of other ways. Safe communities thrive.

I was fortunate enough to spend a few hours geeking out with Matt Duncan, the Operations & Safety Manager for Lakewood, Colorado, a hamlet just south of Denver. He was here for the NCTCD (The National Committee on Traffic Control Devices) which is held about the same time as TRB, but on the other side of town. The hustle and bustle of the Fashion Square Pentagon food court around us was a fitting setting for discussing the busy-ness of a small city.

On site gives you insight.

One of the first things that impressed me as a was that he visits the site of every single fatality, usually within the first day or two afterwards. There are things you find on-site that will never show up in the crash reports.

For instance, they had several run-off-the-road motorcycle crashes over the years at a curve sitting at the bottom of a hill. There seemed to be no good reason for them until he walked it. The superelevation (side-slope) on the curve should have been steering vehicles back into the curve, but had been designed and installed to slope away from the road. The cars handled it ok, but with the extra balance issues inherent in motorcycle operations, too many weren’t making it. Without standing on that curve, there was no way the pictures or diagrams could have pointed out the design issue.

Making friends, bridging silos

When he first arrived 11 years ago, safety was its own little shop and rarely talked to anyone else. One of the first things he did was reach out to the police, who have become an active partner—his eyes and ears. When social services moved their operation to a different part of town, it was the police that called him up for an evening ride along. The new area had almost no lighting and several folks with various “impairments” clustered far too close to the road. He was able to get funding relatively quickly to light up the mile long stretch. An impaired homeless man sitting in the middle of the road building a pile of rocks will be much harder to see without that lighting. Those are the types of issues that we need to recognize happen and will be difficult to remediate without a multidisciplinary, whole of the community approach.

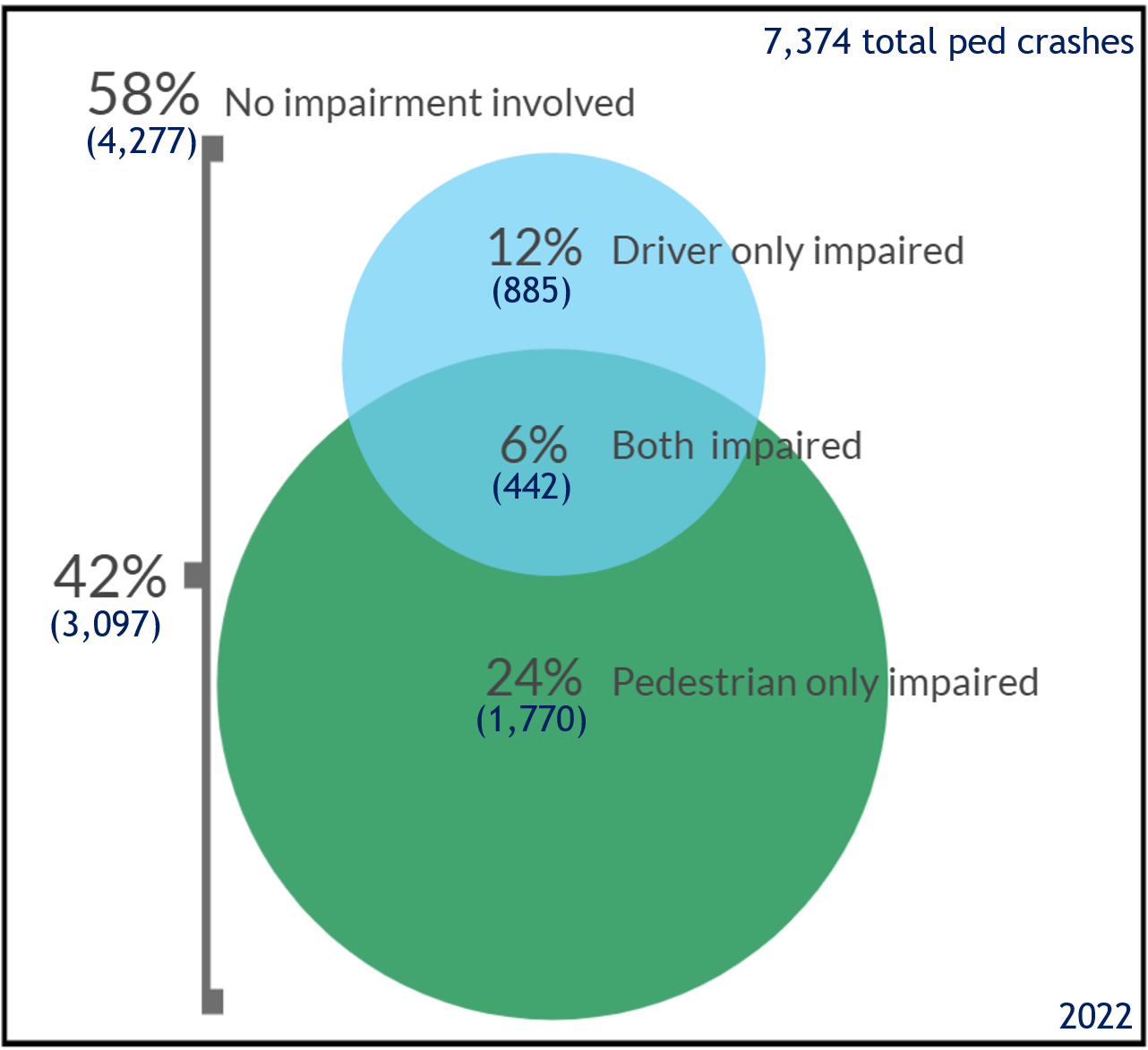

His more recent partner is the coroner. Nationally, it appears that about 42% of our pedestrian fatalities are impaired, but there’s a problem with that data stream. The police are only interested in supporting future prosecution efforts. It takes time and effort to circle back to the coroner to identify whether the pedestrian was impaired. If the victim was responsible for their own death, there’s no reason for them to take that time away from their other duties—they have other things to do. Any untimely death triggers an autopsy in Lakewood, so the data exists—that’s not always the case throughout the country—and the coroner feeds that data back to him. They’re showing that 92% of their pedestrian fatalities are impaired. It’s possible that’s unique to Lakewood, but how do we know unless we start checking?

Getting technical about impairment patterns

One issue the coroner and police have reiterated is that the type of impairment matters. Different parts of town will have different impairment patterns. The meth, fentanyl and crack seen in areas where there is a problem with chronic homelessness is different than the prescription drugs, cocaine, and marijuana use that pops up in more affluent parts of town.

The drug types make a difference in the person’s behavioral pattern. Someone on alcohol, cannabis, or opioids may be pretty out of it. Their reaction time is going to be a lot slower and their awareness of the environment is diminished. Those on cocaine, meth, or other stimulants feel the anxiety of too much coffee but a hundred times worse. As he described it, “They blow through the sobriety testing. Any pause or wait is infuriating. They want to cross “NOW” and they want to cross HERE and they need to be THERE. Their mind is racing, racing, racing, racing and THAT driver coming downstream is getting out of MY WAY.” In these cases we need really good lighting and edge lines. It breaks the retroreflectivity of the line when they enter the roadway in the dark—which happens suddenly, unlike alcohol or depressants where they generally stagger or fall.

Impairment also makes them much more likely to die at the same impact speed. Alcohol impairs clotting, making concussions worse. Stimulants weaken the heart. Homelessness often happens because of underlying health issues and medical expenses—in addition to the health toll that not eating or sleeping will cause. The impairment itself can slow their reflexes so they’re less likely to brace themselves in a fall, which makes head injuries more common. These are truly vulnerable users in every sense of the word.

Technology solutions

When Matt arrived, there were only 5 intersection cameras and the signal timing was a hot mess. He has an advantage over many of the newer areas in the US. The north area of Lakewood has a beautiful 1/8th mile grid. That provides great redundancy when you truly need it, but that redundancy can cause problems if the main roads are slogging along. There are few places with an 1/8th mile grid that are dense enough to generate serious congestion on anything but the through paths. You can pack a lot of land use in something that redundant and no one suffers.

One of the first thing he did was retime the signals along the major corridors. Because he has that spacing, it’s easy to get a uniform progression of 33 mph, which drops driver’s blood pressure, calms tempers, and evens out the speed profile. After the retiming, crash rates on dropped on the main arterials, but he also lost the irritating little crashes on the side streets. Network redundancy provides resilience to system failures, but if you can keep things flowing on the arterials, the cut-through we’ve been trying to avoid isn’t a problem.

He has also gone thfrough most of his signal installations and cleaned out all but the essential wayfinding signage. The extra retroreflectivity flashing back at the driver distracted from the signals themselves.

He’s now got 400 intersection cameras recording and he saves the footage around many of the crashes so he can go over them to identify what happened and why. Although that would normally raise privacy red flags, few people will complain about using the data for this purpose. They know traffic cameras are there to manage traffic.

Over the next few months we’re hoping to look at the difference between the daytime and nighttime crashes. One of the things that I noticed in the time of day data was that fatal pedestrian crashes had a huge night component, but serious crashes were happening all day long. Here’s what I pulled down from Signal4 in Florida:

My suspicion is that the difference between a serious crash and a fatal one is those last few moments of braking before the collision. It makes sense, but no one has checked (that I can tell—let me know if I’m wrong on that). He’s got footage from those crashes so we can tell when the braking happens and the speed the collisions happen at. We both get busy, so pray we can get around to it.

No superheroes…just do the work

Matt is probably not all that different from many other traffic engineers around the country. He has lots to do, but he cares about the people he serves—as you do. He may never get to Vision Zero. Most doctors will not see their patients live forever either. That’s no excuse to stop trying.

What is in your control is your responsibility, and that may be far more than you realize. Having a fatality “in the family,” so to speak, has been a wake-up call for everyone within their local government agency. I’s the kind of emotional gut check that can get people aligned in ways that move mountains. He talked with the family about how much privacy they wanted before he started talking about it among the departments. No one wants to have them feel like we’re using their pain to advance our agenda. The family was adamant that it was a story that needed to be told. This type of storytelling has been one of the main commonalities in all the communities I’ve seen succeed at Vision Zero: someone stopped long enough to see these fatalities as people, not just a number.

It’s easy for fatalities to become a statistic instead of a story. Stories that move hearts are not over—and if it’s not good yet, the story hasn’t finished.

Sure, there are social issues that underly our problems, but every person we lose is someone’s family. Each of the 38 fatalities he’s had to deal with are unique and required unique remediation strategies. I encouraged him to pitch in and push back on the ITE boards when he sees folks describing things that don’t match his experience. We all see different problems and it’s time to replace our arguments with a

“yes, and…”

approach to seeing each other’s issues. Your problem could be totally different, but you also may recognize something in their observation that you haven’t noticed yet. You can’t start counting what matters until you recognize what you need to count.

But I already have a lot to do!

I can already hear folks complaining that they don’t have the time to execute this level of care. You may be working in a much larger jurisdiction with a lot more fatalities.

Start somewhere.

Strong Towns has created crash analysis studio processes that is modeled around the 360 degree evaluations used in medical cases. You can apply this process to your hot-spots as a start.

You can make friends with the experts in other silos.

Share your data when you come to conclusions. It may not make it into a journal, but if it makes it onto the professional discussion boards, it may get more traction in practice anyway. Researchers want long bibliographies and lots of cited papers, but few practitioners ever see that research and even fewer see the process of moving that research into standards. Practitioners need to see the successes and failures from the field—stories—to deal with this problem now. I recently saw a post on LinkedIn showing an orthopedic surgeon spending his Sunday morning pouring over journal articles so he was better prepared to deal with his cases. Those of us who straddle research and practice try to translate the most effective research, but the quantity can seem overwhelming. The conditions are changing too quickly for research to keep up now anyway. Sharing your own experience is the best way to get the word out on what is working, what isn’t working, and why.

This has been going on too long for us to call it a crisis, but it certainly feels that way when it hits home.

Up Next:

It’s probably time to do a series on my main mental model for systems analysis. I have a series of seven archetypes that seem to work better than anything else I’ve ever seen and it applies to systems at all scales from molecules to galaxies. This series may be more generally applicable than the transportation stuff I usually write about, but I’ll make sure there’s something useful for my transportation geeks as well.

Of course, if you haven’t taken a look at the Mental Frameworks summary, it’s probably time to check it out.

See you next week.

Really glad to see these sentences: “My suspicion is that the difference between a serious crash and a fatal one is those last few moments of braking before the collision. It makes sense, but no one has checked (that I can tell—let me know if I’m wrong on that). [Matt’s] got footage from those crashes so we can tell when the braking happens and the speed the collisions happen at.”

I’ve wondered about this issue and asked a couple of traffic pros without getting any answer: When stats refer to “a 90% fatality rate at 50 mph” or a “20% fatality rate at 25 mph”, or similar stats, does this mean the vehicle is traveling at 50 mph at the moment of the crash, or that the vehicle was traveling at 50, but likely slowed to some degree before the impact? And the response has been “That’s a good question, and I have no idea.” So I’m glad you, and Matt, are aware of how important this is, and doing your best to get answers.

I also agree that collecting data on pedestrian impairment is an essential part of understanding the whole picture – but I don’t like the implication that, to an investigating officer, an impaired pedestrian “was responsible for their own death.” Being impaired doesn’t merit the death penalty. And among the differences between a careful, sober driver and an impaired pedestrian, there’s this difference: the driver is doing something that’s inherently dangerous to the public, while the pedestrian is not.