Framework 2: People get Priority (neurologically)

Our driving may be mindless, but seeing people changes everything.

If you meet me in person, I’ll probably call you “Beautiful” or “Handsome”—often before I’ve even looked at your face. I’m not hitting on anybody (seriously, there is enough drama in my world—I don’t need more). I genuinely believe that people are the most beautiful things I ever see. They can also be the most frightening, intimidating, and overwhelming things around us. Just ask a person with autism—many times they avoid looking at faces, not because they lack empathy but because faces are so emotionally threatening and overwhelming. We are worthy of awe and they may be the only ones who really get that—seeing the Imago Dei should engender awe.

When William Whyte studied park space in New York City, his final conclusion was;

“What attracts people most, it would appear, is other people.”

In an urban space, the face-to-face interactions drive everyone’s behavior. This is hardwired into us. Nothing is more neurologically compelling than seeing, hearing, and interacting with another human being. We all have an amazing amount of neurological real estate dedicated to seeing people and understanding their emotional state.

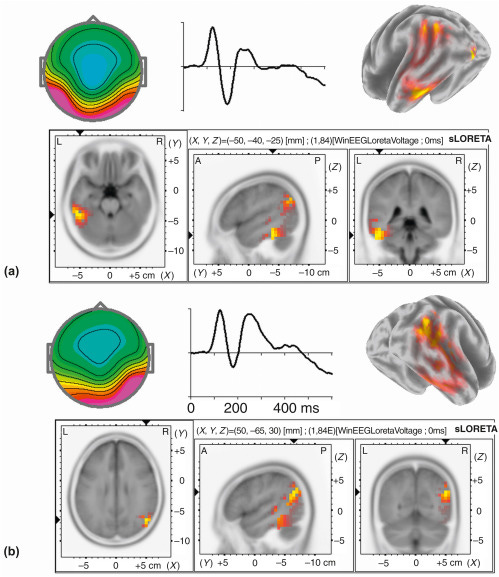

There’s a spot in our brain that does nothing but read faces. There’s other areas that look for body language. There’s a very repeatable brain wave pattern that pops up at 170 milliseconds when you see a face called the N170 wave—that’s long before you are conscious of seeing it at 300 milliseconds—that’s called the P300 wave. A similar pattern for body language pops up at 190 milliseconds in a nearby area.

There’s two huge stripes down the middle of your brain that map out your body sensations—and it lights up like a mirror when it sees other bodies doing things, as if it were the one doing the movement. Processing these faces (and bodies) uses nearly every major section from the prefrontal cortex to the innermost parts of the midbrain. Most importantly, the amplitude of the N170 facial recognition wave is directly tied to the intensity of the emotion you’re seeing. What the brain is trying to figure out is whether that person is a treat or a threat.

This is a part of the brain that gets developed very, very early. Rob a baby of human interaction in infancy and they may never get back all of what that time lost—the orphanages in Romania taught us its devastating effects. The most distressing human experiment I’ve ever witnessed was the still face mother experiment. Two minutes of being ignored is an eternity for a baby.

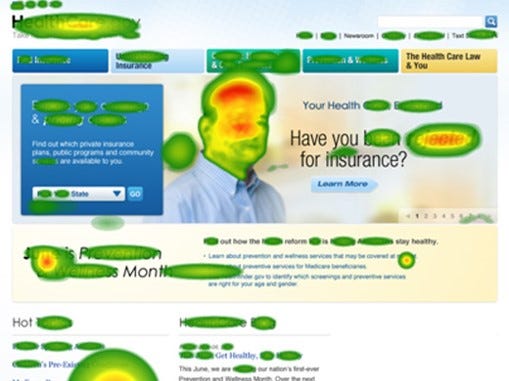

When you look at pictures, you see people first and you come back to them. When researchers showed people pictures with a face in it, 2/3 of the time the first fixation was on the face. If you map fixations in advertisements, people usually land on the faces first and spend the longest time on them, especially the eyes. If the face is ugly or disturbing, they still look at them early and often, but only furtively—glancing at them, but spending much less time fixating on them, though they’re just as memorable.

It’s not just faces. There’s a massive line of psychological research that looks at biological movement—over 1500 articles on Google Scholar. Point Light Walker research uses a series of dots on the major joints and body parts to represent a person as they move. These representations are so easy to pick out, researchers have to mask the effect with extra dots or dropped body parts to measure it—and it usually takes a lot to make the effect go away. If it moves like a body, it pops out in the visual field.

So why do faces and bodies draw such attention?

From an evolutionary standpoint, it’s obvious. People are going to be your best assets and your biggest threats. By the time a baby is 6 months old, they can distinguish between human faces but they quit discriminating between monkey faces. If they mess this up, it’s not a mistake that ends well.

Some of the earliest stages of developing empathy are driven by a baby’s reflexive ability to mirror back facial expressions. As they generate those expressions, they experience the emotions tied to them, feeling the emotional state of those they see in real time.

From a neurological standpoint, faces and bodies trigger chemical reward (and threat) signals using dopamine and norepinephrine. Neuroscientists figured this out in the most tragic of ways. As people descend into Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s related dementia, they lose the ability to recognize faces—not just recognize familiar faces, but the ability to recognize that something is a face. This has devastating emotional consequences, not just for the family members but for the person who is now locked in an increasingly lonely world.

What does this have to do with driving?

Last week, we talked about how most of our driving is done by automatic systems that respond very quickly and is trained by experience (Khaneman’s System 1). The brain systems that get the most training on this are the human perception systems we’ve been talking about. Remember, the purpose of our automatic, System 1 thinking is to monitor the world around us for danger and rewards: treats and threats.

We don’t stop being human just because we are driving, though if you ask someone walking nearby, they may beg to disagree. Researchers found that the way pedestrians talk about cars was completely dehumanizing: the danger was from the “car” or “vehicle” not the drivers. What do those pedestrians recognize that we’re missing here?

So why doesn’t this seem to make a difference when we’re driving?

There’s a good reason and it has a lot to do with whether or not System 1 thinks it’s important—but that’s all covered in Framework 3, which we will talk about next week.

Hint: speed and scale make a big difference.