Framework 1: Driving is automatic

Once you learn to drive, you quit watching yourself do it, and that's good.

If you’ve ever taught someone to drive, you know what I mean.

My son is one of the safest drivers you will ever meet. (I am not—that’s why I do this type of research). When he went to college, I went back to grad school to get my PhD, so we drove together across town. After the first year, he decided that I was no longer driving because I wasn’t trustworthy (smart kid). I wanted the time to read anyway (smart mom.)

I remember teaching him to drive. It was painful for all involved (including anyone who had to watch). We did the normal parking lot thing. I found him the narrowest drive through bank teller area I’ve ever seen and made him thread through it half a dozen times or more. We parked. We drove around the quiet streets. We drove around the busy arterials. We eventually did the Turnpike. I picked times when things were pretty calm (if I could find them). I do not envy this generation as they learn to drive. It’s a lot harder now. He struggled like everyone else does. It was a long time before it was comfortable for him or me.

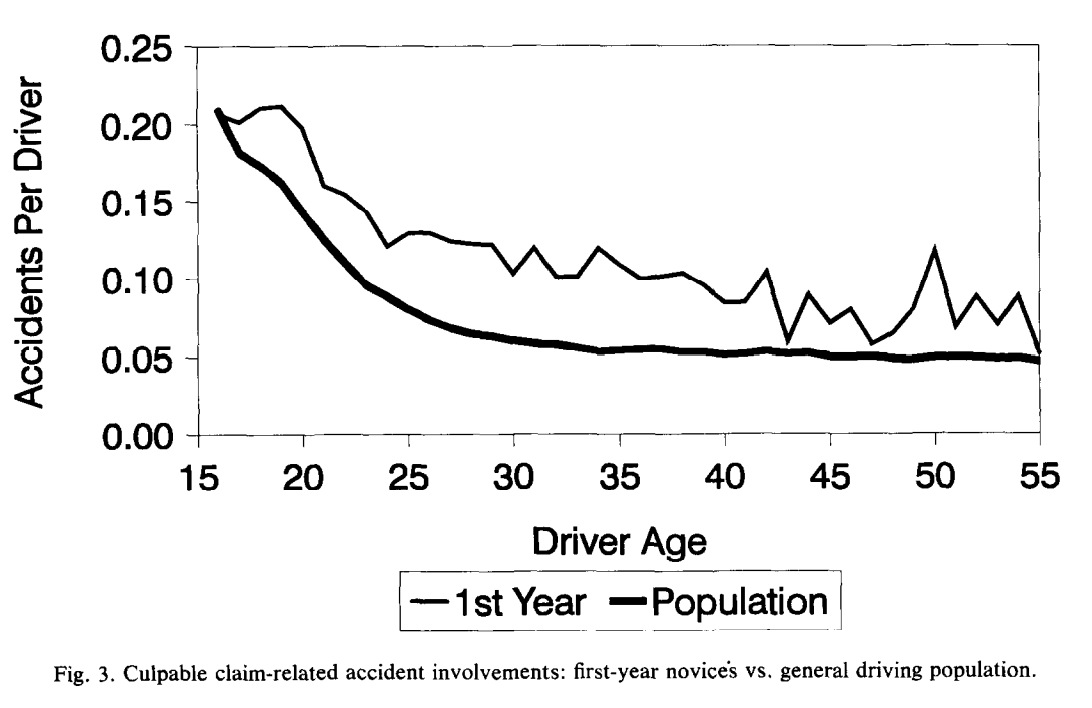

Turns out, it’s not just that they’re young. Maturity does make a difference, but everyone has a higher crash rate when they’re first driving (1-2). The first few months are brutal, statistically (3), but It takes about 3 years to really settle in. As it does, crash rates drop about 40% and keeps falling until their maturity catches up with their skill set.

What’s wild is that as novice drivers gain experience, they get sloppy. Their trajectories show more near misses, errors, and outright violations (4), but that doesn’t translate into more crashes. Here’s the reason:

There are two major systems in your brain. We call them System 1 (thinking fast) and System 2 (thinking slow). System 2 isn’t the one driving anymore.

The primary researcher in the field even wrote this amazing book to summarize their differences.

System 2 is what we think of when we think about thinking. It’s logical, sequential, verbal, analytical, and a little bossy. This is the part that reads and does math. You can watch what it’s doing (metacognition) and probably write it down. No matter how quick on your feet you think you are, it’s still about half as fast as System 1.

System 1 is a different type of bean counter, and it is very good at statistics.

It’s job is to keep you alive, fed, happy, and out of pain. It is very fast—it runs in 10ths of a second, not full seconds. Mostly it learns to play the dice by repeated experience. That means the more experience it has to work with, the faster it can make a response. That’s why your driving gets sloppier as you get more experience. Your System 1 brain has figured out where you can cut corners without running into something. You know where to look and you know where you don’t need to look because it hasn’t been important.

System 2 might be the part that thinks, but System 1 is the part that drives—and you want it that way.

I even saw a study once that showed that when they trained drivers to maintain their full, conscious attention on the road, their lane keeping, car following, and speed maintenance got worse, not better (5). You want your automatic brain to do the driving (but not check out entirely—that’s another issue).

This generates some interesting abilities. You stay in the lines by monitoring them with System 1 in your ambient vision. That’s a cone of sight that covers about 30 degrees from center. You don’t need to stare at the lines to stay in the right place—as long as you’re looking in that general direction, lane keeping stays pretty solid. You also know exactly how much road is likely to give you issues and you watch an area that is big enough to fit what we needed when we were walking around (more on that in a few weeks). System 1 also decodes symbols pretty easily. It turns words into symbols if they’re common enough but it doesn’t read, per se. System 2 can shout down to System 1, but that’s the long way around. Your brain is not a fan of wordy signs.

In other words, the part of the brain that drives is not the part of the brain that reads.

This is not necessarily mindlessness. System 1 is not unconscious—but it is often sub-conscious. One of my friends, Dr. Charlton in New Zealand did an interesting study on how much we remember during our driving time (6). He had a researcher drive along with people on a route that was familiar to them. After the driver did something, like a movement or reaction, they would wait and then ask them what they just did and why. If they asked within 30 seconds, the driver could tell them most of the time. If they waited to 90 seconds, none of the drivers could remember what had just happened. If it had been unconscious or subliminal, it wouldn’t matter how quickly they asked, the driver wouldn’t have remembered it. If they didn’t bring the response up into system 2 by talking about it or thinking about it before it was gone, the memory evaporated as if it never existed.

This is an example of the Zeigarnik Effect (7), which was first noticed in restaurant waiters in the 1920’s. As long as the order was still open, the entire order was kept in memory. The moment the table left, they had no memory of their orders at all. When we turn left or swerve around a paused vehicle, completing the maneuver allows that memory to disappear. That’s good because my mind is cluttered enough.

So how does this matter in urban space, specifically? Obviously, highway and arterial style driving depends on this type of automaticity, but why is this different in an urban space? The problem is that when it comes to pedestrians and cyclists, you aren’t in any danger—they are. System 1 doesn’t really care because it’s not their problem. All it cares about are personal treats or threats. That may seem egocentric, but that’s it’s job. It’s the part that puts the mask on yourself first so you’re still conscious enough to put the mask on someone else. System 2 does care and might see them but may have to holler down to System 1—often far too late for it to respond well.

But don’t despair! This is where some reflexive hardwiring can interrupt your selfish System 1 Statistician. Your brain craves all kinds of things like novelty, connection, and food. System 1 will reflexively look out for those things without your conscious awareness— and that has serious implications for urban environments.

That’s what we’re going to talk about next week, so stay tuned and subscribe!